Inheritance Guide for Heirs (Canada)

When a parent or someone close to you passes away, it can be an emotional time. Compounding the feelings of loss can be the uncertainty of what comes next: Who will make the funeral arrangements? Who will handle the decedents belongings? What will be the implications for me?

In some cases these questions may include a concern about immediate living arrangements, in others, about long term financial security, or in still other cases, simply inheriting a personally meaningful memento.

This Canadian Guide for Heirs explains the process of estate settlement, the role that heirs play in the process, and the overall timing of events.

Summary

Note: While most provinces handle estate settlement similarly, please be aware that Quebec handles things differently.

When someone passes away, their possessions are distributed to the rightful heirs after any succession obligations such as debts and various taxes have been resolved. This process is known as estate settlement, and is typically overseen by an executor named in the will and confirmed by the court, or if there was no will, then by an executor appointed by the court.

A person can be entitled to inherit property for a variety reasons. You may be named in the will to receive a specific item (i.e., a bequest), you may be named in the will to share a percentage of the estate, you may be entitled to certain property regardless of the will (i.e., family entitlements), you may be named as a beneficiary of a certain account (e.g., RRSP), and if there is no will, you may be entitled to a share of the estate due to your family relationship with the deceased (e.g., child, spouse).

Most estates go through probate and have an official executor who manages the process:

- Executor Discretion: As an heir, you can make requests of an executor for additional information, or even for certain property distribution preferences, but for the most part the executor is in charge and can do what he or she likes, within the confines of the will and the law. If you feel that the executor is behaving improperly, you can object to the court, potentially changing distribution outcomes and/or having the executor replaced. See also Working with Executors.

- Notification: In some provinces, the executor must notify you of the death, even if you do not stand to inherit anything but would have done so had there been no will. The purpose of this notification is to inform you that an estate settlement is underway, so that you can track its progress, coordinate with the executor, and potentially object to the court if you believe something is incorrect. Depending on the province and details of the particular estate settlement process, it is common for an executor to submit an estate inventory and a final accounting to the court, and often these reports must be distributed to the heirs.

- Distribution Timing: While settlement times vary greatly according to the particulars of an estate, an average estate takes ~16 months to settle. In general, distributions to heirs occur at the very end of the settlement process, in order to ensure that all estate obligations have been met. Executors can be held personally liable if they make distributions and then the estate cannot pay all its debts or taxes, even if those obligations were a surprise and unknown at the time of distribution. While exceptions can be made, estate executors are advised NOT to make any distributions to heirs until the tail end of the process. See also Inheritance Timing.

- Taxes: Among other responsibilities, an executor must ensure that an estate pays any federal and province taxes owed, including those on deemed disposition of all capital assets. See also Estate Expenses, Fees, and Taxes.

- Receipts: When it comes time to receive a distribution from an estate, an heir is often required to sign a receipt for the distribution, and often that receipt requests that the heir give up any rights to sue or object to any aspect of the estate settlement process. You are not necessarily required to give up those rights to receive a distribution, so if you have concerns, you are advised to speak with a lawyer before signing. However, most people simply sign the receipt and receive their inheritance.

If an estate is small, there may be no need for probate or an official executor, and some provinces have simplified procedures for handling such estates, in which case the burden may fall to the heir to collect any inheritance: see Small Estates.

If you are entitled to an inheritance because you have been named a beneficiary of an asset that automatically transfers on death, such as an RRSP or a life insurance policy, then any executor will not normally be involved at all. You will likely have to fill out a few paperwork items and should automatically receive your inheritance within a few weeks.

See Steps to Inherit for more information about the 4 primary inheritance methods.

The Basics of Estate Settlement

Estate settlement is the process of collecting a decedent's assets, resolving debts, paying taxes, filing legal paperwork, and distributing remaining assets to the rightful recipients.

Probate is the court-supervised process of estate settlement, and it is the probate court that appoints an executor (usually in accordance with the terms of the will, if one exists) to manage the settlement process. Depending on jurisdiction and circumstances, the person in charge of this process may instead be called a personal representative, administrator, estate trustee, or estate liquidator, but to keep things simple, we will normally just use the generic "executor" term.

Not all estates require court involvement, but an estate will generally have to go through probate unless it contains only assets that automatically transfer to named beneficiaries, or if the estate qualifies to use one of the province-specific small estate procedures. If an estate does not go through probate, then there will be no official executor, but court approval may still be needed for any transfers of estate assets.

A somewhat simplified view of the overall estate settlement process, from the point of view of the executor, consists of the following overlapping steps:

Estate settlement takes time, and while settlement periods can vary dramatically according to individual circumstances, most Canadian estates take 6-18 months to settle (with more complex ones sometimes taking several years). In addition to all the work of inventorying the estate, selling off certain assets, resolving debts, and so forth, there are often waiting periods mandated by law to give interested parties a chance to notify the estate of relevant information (such as outstanding debts, family entitlement elections, etc.).

Inheritance Factors and Priorities

There are a number of factors that determine estate inheritances, including wishes expressed in a will, province law, designated beneficiaries, legal family relationships, and even executor discretion.

You may be entitled to inherit from an estate if:

- You are beneficiary of an automated transfer

- You are named in a will

- You are a surviving spouse or child of the decedent

- You are one of the closest living relatives and there is no will

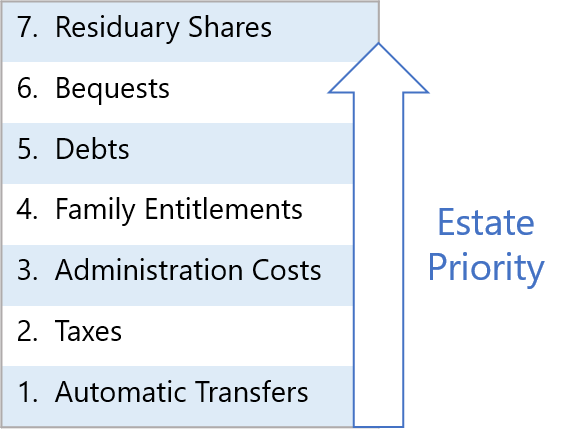

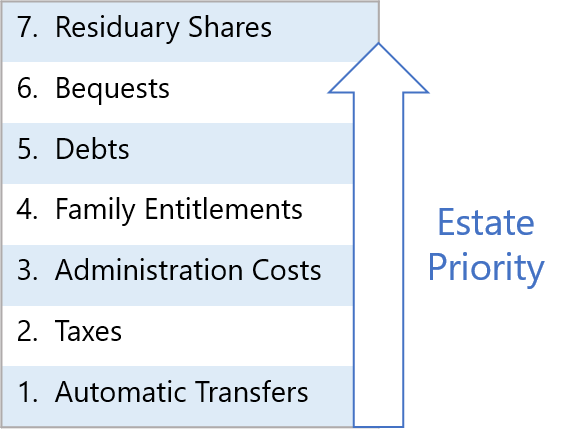

Even if you are potentially entitled to inherit from an estate, however, there may be priority claims on the estate that could diminish or even eliminate your inheritance entirely, including estate debts, tax obligations, heirs with stronger claims, etc.

See Rules of Inheritance for details on inheritance factors and prioritization of estate proceeds.

Summary for Quebec

Note: Please be aware that other provinces handle estate settlement differently than Quebec.

A person can be entitled to inherit property for a variety reasons. You may be named in the will to receive a specific item (i.e., a bequest), you may be named in the will to share a percentage of the succession, you may be entitled to certain property regardless of the will (i.e., family entitlements), and if there is no will, you may be entitled to a share of the succession due to your family relationship with the deceased (e.g., child, spouse).

When a Quebec resident passes away, their possessions are distributed to the rightful heirs by a succession liquidator, usually a family member named in the will who registers with the Le Registre des Droits Personnels et Réels Mobiliers (RDPRM). In most provinces, this process is known as estate settlement, and the liquidator is known as an executor: this Guide will often use the terms interchangeably.

- Liquidator Discretion: As an heir, you can make requests of a liquidator for additional information, or even for certain property distribution preferences, but for the most part the liquidator is in charge and can do what he or she likes, within the confines of the will and the law. If you feel that the liquidator is behaving improperly, you can object to the court, potentially changing distribution outcomes and/or having the liquidator replaced. See also Working with Executors.

- Notifications: The liquidator is required to notify you (as someone who will inherit, or who would inherit if there were no will) of the closure of the inventory (i.e., the complete contents of the succession), and the closure of the liquidator's account (i.e., the financial details of the succession process). The purpose of these notifications are to inform you that a succession is underway, so that you can track its progress, coordinate with the liquidator, and potentially object to the court if you believe something is incorrect.

- Distribution Timing: While settlement times vary greatly according to the particulars of a succession, an average succession takes about a year to settle. In general, distributions to heirs occur at the very end of the settlement process, in order to ensure that all succession obligations have been met. Liquidators can be held personally liable if they make distributions and then the succession cannot pay all its debts or taxes, even if those obligations were a surprise and unknown at the time of distribution. While exceptions can be made, liquidators are advised NOT to make any distributions to heirs until the tail end of the process. See also Inheritance Timing.

- Taxes: Among other responsibilities, an executor must ensure that an succession pays any federal and province taxes owed, including those on deemed disposition of all capital assets. See also Estate Expenses, Fees, and Taxes.

- Receipts: When it comes time to receive a distribution from a succession, an heir is often required to sign a receipt for the distribution, and often that receipt requests that the heir give up any rights to sue or object to any aspect of the succession process. You are not necessarily required to give up those rights to receive a distribution, so if you have concerns, you are advised to speak with a lawyer before signing. However, most people simply sign the receipt and receive their inheritance.

See Steps to Inherit for more information about the 3 primary inheritance methods.

The Basics of Liquidation

Estate settlement is the process of collecting a decedent's assets, resolving debts, paying taxes, filing legal paperwork, and distributing remaining assets to the rightful recipients. In Quebec, this process is known as liquidating a succession.

A somewhat simplified view of the overall succession process, from the point of view of the executor, consists of the following overlapping steps:

Estate settlement takes time, and while settlement periods can vary dramatically according to individual circumstances, most Canadian estates take 6-18 months to settle (with more complex ones sometimes taking several years). In addition to all the work of inventorying the succession, selling off certain assets, resolving debts, and so forth, there are often waiting periods mandated by law to give interested parties a chance to notify the succession of relevant information (such as outstanding debts, family entitlement elections, etc.).

Inheritance Factors and Priorities

There are a number of factors that determine who receives successions, including wishes expressed in a will, province law, designated beneficiaries, legal family relationships, and even executor discretion.

You may be entitled to inherit from a succession if:

- You are named in a will

- You are a surviving spouse or child of the decedent

- You are one of the closest living relatives and there is no will

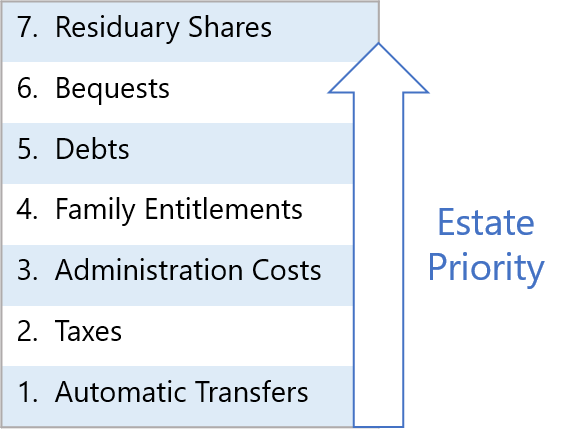

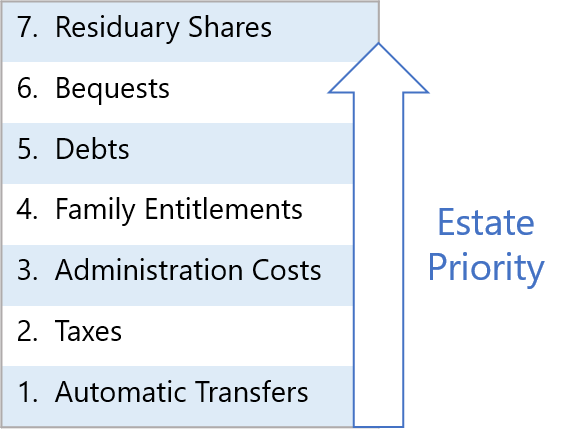

Even if you are potentially entitled to inherit from a succession, however, there may be priority claims on the succession that could diminish or even eliminate your inheritance entirely, including succession debts, tax obligations, heirs with stronger claims, etc.

See Rules of Inheritance for details on inheritance factors and prioritization of succession proceeds.

Key Topics

You can click the links below, or in the table of contents to the left, to learn more about key aspects of the inheritance process.

- Steps to Inherit

- Rules of Inheritance

- Expenses, Fees, & Taxes

- Heir Rights

- Inheritance Timing

- Working with Executors

- Heir Financials

- Glossary

EstateExec™ Leaves More $ for Heirs!

EstateExec will likely save the estate thousands of dollars (in reduced legal and accounting expenses, plus relevant money-saving coupons), leaving more funds for distributions to heirs.

- Awarded Best Estate Executor Software in North America at the Worldwide Finance Awards

- Named Best Estate Executor Tool – – by Retirement Living

- Web Application of the Year Winner at the Globee Business Excellence Awards 2022

- Winner of Best Executor Software at the Software and Technology Awards

- Rated 4.9 stars – – on TrustPilot reviews