Making Estate Distributions (AB)

An estate distribution is the delivery of cash or an asset to a given heir. After resolving debts and paying any taxes due, the executor should distribute the remaining estate to the heirs in accordance with the instructions in the will (or as dictated by the court).

General Plan

Before making any distributions from

After ensuring you have inventoried all assets, including their ownership types and valuations, and have been informed of all estate debts, it's usually easiest to try to plan things in this order:

- Record Automatic Transfers — Define distributions for assets over which you have no control (i.e., RRSPs, life insurance policies, etc.)

- Account for AB Family Entitlements — Define distributions for any Family Entitlements that will be utilized

- Allocate Bequests — Define distributions for any specific bequests made in the will

- Prepare for Debt Resolution — Ensure you will have enough cash to resolve the debts, planning to sell assets if necessary

- Determine Executor Compensation — Decide the amount of executor fee you will take, as prescribed by AB law

- Mark Assets for Sale or Distribution — Plan remainder of asset disposition

- Allocate Distributions — Define distributions so that each heir will get the proper share of the final estate

If the estate will not have enough free cash to resolve all debts, even after liquidating all available assets in step 5, you may need to revisit some of the earlier steps in an attempt to satisfy estate creditors, since debts generally have precedence over other estate claims.

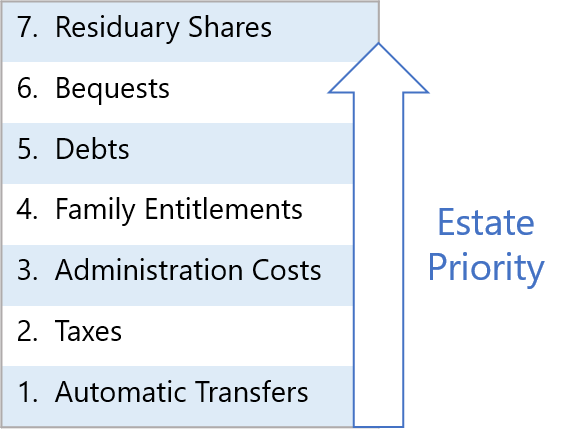

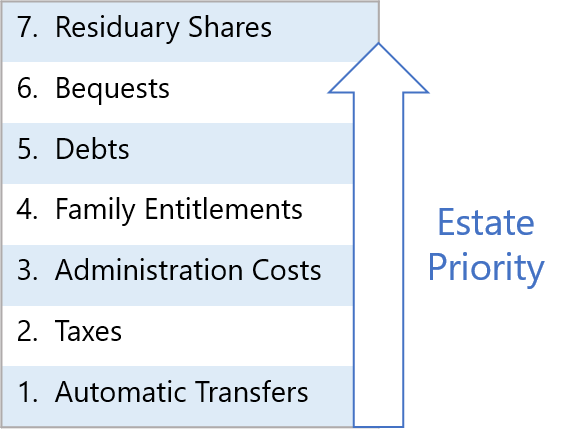

The steps outlined above work well for an estate that can ultimately pay its bills, but if not, you will need to keep in mind that an estate must give preference to its obligations in a defined priority order (see diagram). Certain transfers (such as to RRSP beneficiaries) happen automatically outside the control of the estate, and the estate itself must then ensure it has enough funds to pay all taxes, then estate administration costs (including executor fees), then any family entitlements, then any general debts, and with anything left over, fulfill any bequests, and finally distribute the residuary estate. If the estate runs out of money handling one priority, then subsequent priorities are left with nothing.

Note that provincial law determines which debts have priority over other debts, and some debts (such as funeral expenses) often have priority over family entitlements, but these specifics really only matter if the estate cannot pay all its bills (see Insolvent Estates for more details).

EstateExec makes the overall planning process easier by allowing you to mark whether you plan to sell or distribute each asset (see Reference: Asset Planning), and to define proposed distributions to each heir before actually making them (see Reference: Manage Distributions). You can then see at a glance which assets and heirs need more attention, and the Overview tab will show you overall estate progress.

Automatic Transfers

Certain items change ownership or pay out "automatically" upon death: life insurance policies, property held in joint tenancy or community property with right of survivorship, funds in an RRSP or LIRA for which a beneficiary was named, stocks held in a transfer-on-death account, and so forth (note that in Quebec, only life insurance contracts can transfer this way). An executor does not take possession of such items, or control them, but frequently ends up facilitating their transfer (contacting the organizations, providing copies of the death certificate, etc.). While such items are not subject to AB probate, they can impact the estate settlement process (in terms of taxes owed, calculating certain family entitlements, etc.).

Tip: EstateExec understands that such assets are not usually subject to AB probate, and will automatically handle them accordingly (you can manually override this if desired; see EstateExec Reference: Identify Assets Subject to Probate). In any case, you should create Distributions for each such item with the "Reason" identified as "Automatic".

Family Entitlements

Alberta allows a surviving spouse to claim certain entitlements:

Homestead

A surviving spouse is entitled to remain in the family homestead for life, even if the will or intestate law transfers some or all of the property to other persons (see Alberta Dower Act, RSA 2000, c D-15, s 18).

If a life estate is not elected or is inapplicable, a surviving spouse or partner who is not registered on the certificate of title as an owner of the family home, but who was ordinarily occupying it at the time of death, is entitled to continue living there for 90 days (see Alberta Wills and Succession Act, SA 2010, c W-12.2, s 75).

Personal Property Exemption

When a surviving spouse is granted a life estate in a homestead (see above), the surviving spouse also gets a life estate (the ability to use for life) in the following personal property:

- Food required by the spouse and any dependents of the decedent for the next 12 months

- Up to $4,000 in necessary clothing

- Up to $4,000 in household furnishings and appliances

- Up to $5,000 in one motor vehicle

- Required medical and dental aids

- Up to $40,000 in one mobile home if that is the principal residence

See Civil Enforcement Act, RSA 2000, c C-15, s 88 and Civil Enforcement Regulation, Alta Reg 276/1995, s 37(1).

Family Support

If the portion of the estate that would normally go to a family member is inadequate for his or her proper maintenance and support, the court may reallocate intended estate distributions to resolve the situation. In order for the court to intervene, an application for such support must be made within 6 months after the grant of probate or administration, or before the estate is completely distributed in any case. See Wills and Succession Act, SA 2010, c W-12.2, s 88 et seq.

Family Property Election

A surviving spouse can optionally apply for a family property order to have certain property declared to be owned by the decedent, and the rest by the surviving spouse. Property declared to be owned by the surviving spouse is excluded from the estate, and therefore any disposition by will or intestate succession.

To make such a family property claim, the surviving spouse must file an application within 6 months of a grant of probate or administration.

Family property determination can be complex, and falls to the judgment of the court. You are advised to seek the help of a lawyer if you wish to pursue this route.

Specific Bequests

Wills sometimes specify that certain assets or dollar amounts are to be distributed to certain heirs. Such bequests should be generally be handled before dealing with the residuary estate, in which percentages of the remaining estate are allocated to the appropriate heirs. You can mark these bequests via the Distribution dialog (see Manage Distributions).

However, not all bequests can be honored: sometimes the asset is no longer part of the estate; sometimes the bequest conflicts with local law (e.g., community property); sometimes the asset must be sold (as a last resort) in order to pay estate debts.

The process of reducing bequests is called abatement, and any required reductions are typically made proportionately to the recipients. For example, if the estate is worth $50K and there are several bequests that total $100K, all bequests would be reduced by 50%. Similarly, if the will bequeaths three pianos to a particular heir, and there are only two pianos in the estate, then the heir would receive just two pianos. And if there were no pianos in the estate, then that bequest would remain unfulfilled (known as ademption). Even if the estate has plenty of money left over, the executor cannot "make up" for an abatement or ademption; in this example, the executor cannot buy the heir a piano using other estate funds, or just provide extra cash in lieu of the piano.

Heir Percentages of the Estate

Wills usually specify a percentage that each heir should receive of the residuary estate

(the residuary estate is the amount remaining after all debts and obligations have been satisfied, and any specific bequests handled).

For example, if

If there is no will, then AB law will dictate the heirs and associated residuary percentages.

Residuary percentages do not need to be realized as single lump sum cash payments, but may be composed of multiple distributions, in various combinations of cash and property.

Tip: You can enter these target percentages on the EstateExec Heirs tab, and as you define distributions, see how you are doing in reaching these targets in the Heir Target Allocation chart on the Overview tab (for additional tips, see EstateExec Reference: Manage Distributions).

Heir Debts

In some cases, a decedent dies with an heir (or multiple heirs) owing the decedent money. As an executor, you do not have legal authority to simply forgive (i.e., cancel) such debts: it would be unfair to the other heirs. The heir to whom the money was lent can either repay the estate the amount owed, or you can distribute the loan as an "asset" to some other heir, or you can deem that such repayment has been made as a portion of the inheritance otherwise owed that heir. For example, if an heir owes the estate $10K, and is entitled to $50K in distributions from the estate, you can distribute that $10K loan "asset" to the heir, and plus $40K in other distributions.

Charitable Donations

A charitable donation is really just an estate distribution to a particular type of heir (a charity). The executor does not have the right to give away items of value to charities unless specifically authorized by the will or the court.

Distribution Completion and Receipts

Actually making distributions to heirs is usually one of the last things the executor does in settling the estate. Although it is best practice to make all the distributions at the end of the process, it is usually permissible to make some distributions earlier if desired (see Early Distributions).

It is good practice to require all heirs to sign a receipt for any distributions (the receipt can cover multiple items). When making final distributions to an heir, it is also good practice to have that person sign a document (perhaps prepared by a lawyer), stating that he or she approves of your actions as executor and confirms that he or she has received everything due.

Note that for real property, you will have to register the transfer with the local land registry, and that for vehicles, you will have to register the transfer with organization that issues driver's licenses.

Additional Information

See also EstateExec Reference: Manage Distributions for specifics about using EstateExec to organize, plan, and document distributions that satisfy the directives of the will (and/or the court).

In case you're interested, details about making distributions in other provinces can be found here: