What is an Estate Executor?

Show Table of Contents

An estate executor is a person responsible for settling a decedent's estate. Often the estate executor is an adult child or other close relative of the decedent, but may be a professional lawyer, just a friend, or in fact, anyone named as executor in the will or appointed by a court.

Alternate Terms

An executor is also sometimes referred to as:

- Executrix: The term "executrix" may be used when the executor is female.

- Administrator: If the decedent died without a will, the court-appointed executor is known as the estate "administrator".

- Personal Representative: A number of jurisdictions, particularly those that have adopted the Uniform Probate Code, now refer to both executors and administrators via the broader term "personal representative".

To keep things simple, EstateExec documentation normally just uses the generic "executor" term.

Duties and Responsibilities

At the highest level, an executor is responsible for managing and winding down a decedent's estate: discovering, protecting and managing the assets of the estate, filing required legal paperwork, resolving debts, paying any applicable taxes, and distributing the net assets to the heirs in accordance with the will, or in accordance with applicable statute if there is no will.

An executor has a fiduciary duty to fulfill those responsibilities with the best interests of the estate in mind, to follow all applicable laws, and to act with the highest ethical standards. An executor is not required to be perfect, however; most states require that an executor simply follow the standard of a "reasonable, prudent individual".

See Key Duties for more information about an executor's overall duties, as well as information about how EstateExec constructs a customized task list, including due dates, for your estate. See also Timeline for a discussion of executor tasks by time period, and Executor Checklist for a quick list of standard tasks.

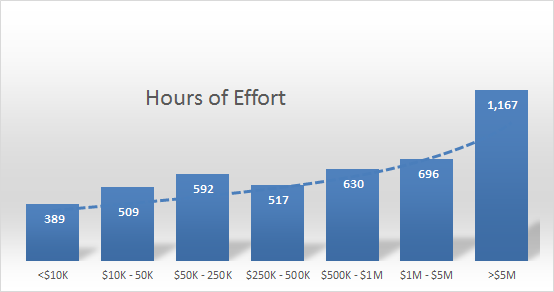

Effort

Serving as an executor usually requires significant effort: on average it takes 16 months to settle an estate and requires 570 hours of work (this effort varies somewhat by size and complexity of estate). See General Statistics for more information.

Risks

The role of estate executor comes with an element of financial risk.

An estate executor can be fined by the courts or sued by other parties for failing to properly fulfill his or her duties. You can be sued for anything, of course, but legitimate grounds for lawsuits include failure to act in a timely manner, failure to adequately protect or manage the assets, failure to follow terms of the will (note that following the terms of a will may not always be appropriate or even possible), engaging in illegal activities, and more.

Executors can be held personally liable for mistakes that result in losses for the heirs. Courts often require an executor to post a bond that will pay to cover any damage he or she may cause an estate (although such bond requirements are often explicitly waived in wills).

Even if the heirs aren't harmed, mistakes can still be costly. For example, if an executor distributes assets before the entire settlement process is complete, then discovers that there are not enough remaining funds to pay taxes owed (see CPAJournal article) or to pay remaining debts, the executor may be personally liable for fulfilling the remaining obligations (so best practice is to distribute assets only after all other obligations have been met; see Making Distributions).

Finally, note that executors may sometimes have to outlay personal funds to cover estate expenses until they can be reimbursed from the estate (because the executor does not yet have legal access to estate funds, or because estate assets are not liquid, such as the case in which an estate consists entirely of real estate).

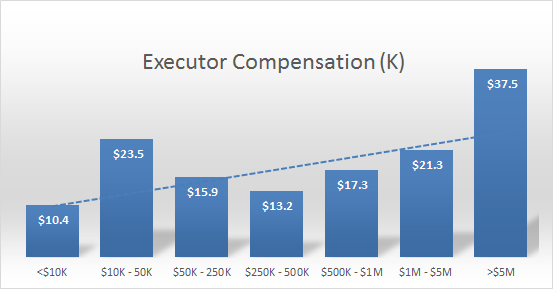

Compensation

Because serving as an executor is so time-consuming and does involve some element of financial risk, executors are generally compensated for their efforts. Laws and accepted practices for this compensation vary dramatically by state and sometimes even local jurisdictions, sometimes being expressed as a percentage of the estate, sometimes calculated in terms of effort expended, and frequently considering additional factors (see Compensation).

Multiple Executors

Sometimes a will names multiple people as co-executors, sharing the burden but also potentially making decisions a bit trickier since all executors must agree on actions.

In some cases an executor decides to step down during the process, or is removed by a court, or passes away him-or-herself. In these cases an alternate executor named in the will, or failing that, an executor appointed by the court, will take over.

Usually compensation is split among multiple executors, often according to effort expended, but some states have specific rules for handle compensation of multiple executors (see Compensation).

Becoming an Executor

Sometimes a person writing a will names an executor in advance, and discusses that option with the named executor (who presumably has a chance to investigate the ramifications and accept or gracefully refuse the offer): see Choosing an Executor.

Sometimes a person writing a will names an executor in advance, and doesn't inform the target person, so the named executor is surprised upon discovering the assignment in the will.

In either case, most states allow a proposed executor to reject the role and step aside if, when the time comes, they decide they would rather not assume the role.

Someone must fulfill the role, however, and the court will appoint someone if no appropriate person accepts the role

See Becoming an Executor for more details about the actual process.